The Curious History of Video Animation

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the first feature length animated film. It was a film called, “Creation” by cartoonist Pinto Colvig, who made the film in 1915. Pinto Colvig, when he wasn’t pretending to mug people while playing off-key tunes on the clarinet, voiced the character of Disney’s Goofy, designed Disney’s logo, and had the privilege of being the original “Bozo the Clown,” among many other accolades.

The film has been lost to the ravages of time, and only a few frames of it remain today. But the art of animation is alive and well. With Pixar using Global Illumination to push the realism of their cartoon films in Monster’s University, and Universal Studios planning to use computer generated imagery (CGI) to bring Paul Walker back from the grave this April, animation isn’t going anywhere either. So, on this particularly unremarkable day in what could be considered a relatively remarkable year, I thought it might be interesting to explore a little of the history of animation.

Every Art Has Its Start

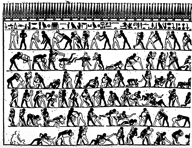

Animation could be said to have the humblest roots of any art-form. There is evidence of it in ancient cave paintings dating back thousands of years. There are animals in these paintings drawn with multiple sets of legs superimposed over each other, and it is likely that these were very early attempts at depicting motion. From these humble roots, in the creation of Egyptian murals and mysterious ancient Chinese devices, humanity’s quest to accurately and artfully record movement through the ages has been ubiquitous and constant.

During the 17th century the fulfillment of that quest began to gain some traction, albeit on a slightly darker level. It came in the form of the “Magic Lantern,” an invention credited to multiple folks, all of whom used it for projecting moving images of demons, monstrous images of the devil, animating normally inanimate objects, summoning ghosts, creating the belief that they could bring the dead back to life and generally just creeping people out. One of its early adopters, a Freemason by the name of Johann Georg Schropfer of Leipzig, ended up driving himself insane from its use. Believing he was pursued by devils, he shot himself after explaining to an audience that he would later bring himself back to life.

With this happy start to animation projection (aren’t we glad Walt Disney was born much later), the world wouldn’t see much change until the early 19th century. But, it is then that we finally begin to see real progress in the art of animation.

Technology and Animation

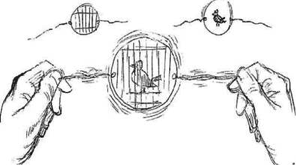

The most popular invention during this time when it came to animation was more of an illusion than a true animation, but it serves as an effective demonstration of the principle which makes true animation possible. It was called a Thaumatrope, and it worked very simply. A small disk with two different pictures on either side was twisted rapidly with strings; twirl fast enough and the separate images would appear to become one. The reason for this is a phenomenon is known as “persistence of vision,” and this is also what causes a true animation to fool us into thinking a picture on a stack of pages can move around on its own.

From there several other inventions were created, each advancing the art of animation projection to exciting new places. The Phenakistoscope, the Zoetrope, the Praxinoscope, and of course the old “Flip Book” technique, were all developed during this time and are great examples of the ingenuity of the era.

Eadweard Muybridge

In 1860, a violent runaway stagecoach crash left a man named Eadweard Muybridge with symptoms of double vision, confused thinking, impaired sense of taste and smell, and other problems. A year later he was an emotional, eccentric artist who’s creativity had been freed from conventional social inhibitions. His medium of choice? Animation.

For the rest of his life, Muybridge dedicated himself to capturing and recording animation. While most of his work was done using photographs, some of them were created using drawings. Some of his books are still published today, and are used as references by artists, animators, and students of animal and human movement.

But it wasn’t until 1908, when a French artist name Emile Cohl created a short film called Fantasmagorie, that the traditional animation methods which guided the production of the likes of Snow White and Looney Toons were finally developed. The film was little more than a stick figure wandering around and bumping into morphing objects (Pre-WWI Transformers, anyone?), but it laid the foundation for the legacies of Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny and a hundred other beloved animated legends.

Make the Cavemen Proud

The rest, as they say, is history. With the groundwork laid, studios like Warner Bros, MGM, and of course Disney, took up the mantel of humanity’s quest and gave the world ACME industries, heartwarming fairy tales, ducks with speech problems, Corporate Monsters, superheroes, action, adventure, romance, and just about everything in between. All while holding us hostage in our living rooms on a perfectly good Saturday morning.